A Good “Machlokes”

by Rabbi Mordechai Rhine

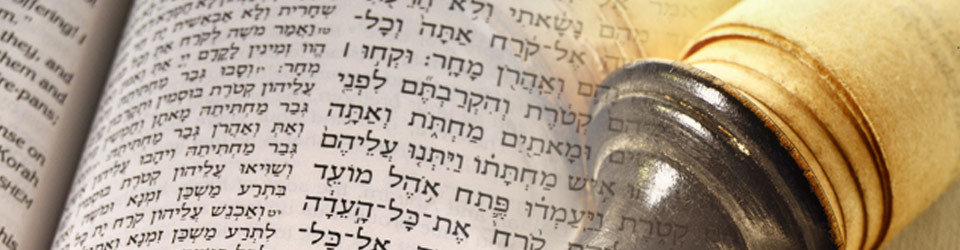

Parshas Korach describes the great argument or “Machlokes” between Korach and our teacher Moshe. Korach felt slighted by the way that Moshe assigned the honors. Korach wished that he had been chosen to be the Kohein. So he started a rebellion. By the time it is over, Korach is miraculously swallowed into the ground, and there is nothing left of his following.

One leaves the topic of “Korach’s Rebellion” feeling that arguments just don’t pay. Disagreements do no good, and leave nothing permanent in their wake. The sages of the Talmud taught otherwise.

The sages in Pirkei Avos observe that Korach’s argument was indeed fruitless. But, the sages insisted, there is a paradigm for an argument that will last in glory for all of eternity. That paradigm is the argument between the House of Hillel and the House of Shamai.

Hillel and Shamai were two of the greatest sages in the Second Temple Era. They disagreed on a few items themselves, but their students disagreed on even more. These two Academies had very different approaches on a variety of issues, yet their arguments did not result in fist-fights or name-calling. On the contrary, their views are recorded side by side for posterity. What was the secret of their success?

I believe the secret lies in a Mishnah in Yevamos (13b) which states: Adherents of the House of Hillel did not refrain from borrowing pots from adherents of the House of Shamai, even though the rulings of one group might be considered not kosher to the other group. The reason they did not refrain, explains Rashi, is because the two groups respected each other. They would never feed anything to a member of the other group which he considered incorrect to eat.

Eventually, the law was codified like the House of Hillel. But until that time, real disagreements existed in the Jewish world. During that time of disagreement there was still serenity in the Jewish world because the two groups respected the opposing views. They could borrow pots with confidence knowing that they would never be given something that was not acceptable according to their view.

In our time it is difficult to find perfect parallels to the Houses of Hillel and Shamai but there are special moments in which we can relive the greatness of those great Academies.

One of my fondest memories growing up in my parents home in Monsey is when my mother offered to make supper for a neighbor in need. I don’t recall if the neighbor was ill, or perhaps during shiva, but my mother went to great lengths to cook the meal properly for this family. You see, this neighbor of ours observed a very strict level of kosher. They observed “Yoshon”.

What is “Yoshon” you ask? At the time, I asked the same thing. There is a law in the Land of Israel that new wheat may not be eaten until after the first days of Pesach. Prevalent practice is to assume that this law only applies in the Land of Israel. It is considered one of the agricultural laws of the Holy Land, and its observance in the United States is not required by the major kosher agencies. Nevertheless these neighbors of ours observed “Yoshon,” and my mother had every intention to accommodate them.

It wasn’t easy to make meatballs and spaghetti for this family. Product codes had to be checked to ensure that the wheat was of a pre-pesach variety. But for all the research, it was a labor of love. When we finally carried the food over to their home, we knew we had done well.

Sometimes we encounter a person who has a view in observance that is stricter than ours. It is entirely possible that our view is also acceptable. But if their view was arrived at as a sincere expression of what they feel G-d wants of them then it should be respected and accommodated to the best of our ability. Views in Torah that are sincere build Torah, they don’t threaten. People who respect a more stringent view ensure that their own view will be granted the blessing of eternity.

© 2015 by TEACH613™

0 Comments