Chanukah: Beyond the Numbers

by Rabbi Mordechai Rhine

The battle of the Jews against the Syrian–Greeks culminated with the miracle of the menorah and the holiday of Chanukah. But the story of Chanukah was not the only interaction that the Jews had with the Greek Empire. For centuries following the conquest of Alexander the Great, the Jews encountered great philosophical differences between traditional Judaism and the Greek perspective. A classic example is the “The translation of the 70.”

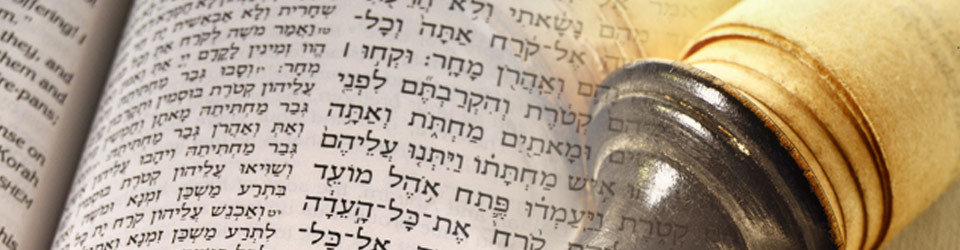

A few decades before the story of Chanukah, Ptolemy, the king of the Southern Greek Empire based in Egypt, insisted that the Jews translate the Five Books of Moshe into Greek. He gathered some 70 sages and had them housed for days in separate tents. Miraculously, despite room in a translation for differences, they all produced identical translations. Ptolemy was quite impressed. But the Jews viewed the event as a tragedy and declared a fast day.

To appreciate why the same event was viewed with respect by the Greeks but as a tragedy by the Jews we must appreciate a major difference of perspective. To the Greek mind, everything was about physicality. Everything was to be measured, quantified, and categorized. To the Jew, however, the physical world is merely a springboard for higher goals. It is the things that cannot be physically quantified that get the most attention in Judaism.

The Greeks saw the Torah and they wanted to conquer it. To the Jew, the Torah text is merely the starting point- the love note- in a devotional relationship with G-d. But the Greek culture wanted to quantify it, to translate it, and to find a place for it in the library. From now on, the Greeks would tell the world that Torah is nothing more than an ISBN number. In their minds they had conquered it; they had managed to contain it to physical dimensions. To the Jew who recognized that Torah is life itself, the incident was a desecration and was commemorated as a tragedy.

Years later, the Northern Greek Kingdom based in Syria attacked the Jews. It was a physical battle aimed at breaking the spirit of the Jew. Although the tactics were different, the underlying philosophy of this conflict was the same as the “translation” encounter. The Greeks had many gods, but they ascribed human, physical qualities to them. The Jew, however, was so other worldly. The Jew so clearly had a relationship with a G-d that had no physical form. This was something that Greek philosophy could not understand and would not tolerate.

Interestingly, the drive of mankind to physically quantify and document things did not end with the Greeks. Throughout his writing, for example, Rambam/Maimonides fought those who ascribed a physical form to G-d. To this day, many try to physically quantify and document things even when it makes them look foolish and silly. But some people find it hard to acknowledge a spiritual dimension.

Take for example an article that appeared a few months ago in a well-read psychology periodical. In it the authors quantified “Love.” They explained that there really wasn’t anything to get excited about. After all, “love” is merely the increase of some certain chemicals in the human body.

While such a physical quantifying of “love” might have great use in the medical treatment of a chemical imbalance or disorder, it became clear from the readership responses that the article had done little to quantify “love.” Love is an experience. It simply is not something that can be captured in a chemical formula or an ISBN number.

Likewise, many scholars get sidetracked by the scholarly documenting of details, and forget to pay attention to the greatness of their subject.

In the 1800s, for example, a significant movement arose in the Jewish world called the Haskalah, or Enlightenment. The driving principle of this divergent movement was its claim to be more worldly and more scholarly than the scholars. With time, however, their foolishness became apparent. As one Rabbi explained, “These Enlightened Jews are so scholarly that they can tell you what our father Avraham wore, and what he ate for breakfast. But my students can tell you what he stood for, and how we can emulate him.”

In our time as well, we have many groups who can tell you the minutia of Jewish culture, but they do not personally practice what they study. In many cases it is the result of a generation who declared themselves “Jews at heart.” They claimed that as long as their hearts were in the right place, nothing else really mattered. But that is a challenging position to take given that Judaism is about relationship. Judaism is a religion of experience.

Recently I had the opportunity to mail a number of boxes to different places across the country. As I did so, I became a bit of an expert on the postal regulations of packages. I knew the measurements of each box (length, height, plus depth) and could tell you which classification each package would be given.

The numbers were very important to me. Yet, I would have been quite disappointed if a recipient had said, “Oh, yes, I received a package today… Rabbi Rhine sent me 98 inches.”

When you try to physically quantify things of a higher dimension, like a gift or a spiritual experience, you end up with misrepresentation and inaccuracy.

The Midrash tells us that the Greek culture is “darkness.” Despite all of their advances in architecture and science, they left the world in emotional and physical darkness. A philosophy that is purely physical takes the life out of living; it takes the joy out of love.

Chanukah is a time to rejoice. The lights that we kindle cannot be quantified or measured. They are eternal lights of the menorah and Jewish living that span the generations, from the victory of Chanukah in the time of the Beis Hamikdash to the living quarters of each and every Jew in our generation.

With best wishes for a Good Shabbos and a Happy Chanukah!

©2017 by TEACH613™

ISBN number. I love the idea – have a great Shabbos

– Naftoli

Beautiful!

All 1,007 words, 18 paragraphs, 4,881 characters (not including

spaces), and 5,869 characters (including spaces).

-Shlomo